Early childhood

Corellistraat, with house Hertzberger family.

'In the Plan Zuid area in 1932, designed by Berlage, I was born and raised. I was born on Churchill-laan and subsequently moved to the somewhat fancier part of Amsterdam Zuid, the area around Apollolaan. My father was a doctor, and I sometimes accompanied him on patient visits, usually in the neighbourhood. As I was not allowed to go inside with him, I would either stay in the car or walk up and down the street and wait for him. That was not always much fun. Without realizing it, I was being given an education in architecture, absorbing in all their detail the doorways, façades, canopies, bay windows and different shapes of windows. The more I practice my profession, the more I realize that I was also absorbing, perhaps more than anything else, the atmosphere of that exceptionally and beautifully proportioned, intimate and yet spacious neighbourhood. The urban space, that particular urban structure so characteristic of Berlage. He hardly built anything there himself, but he did lay down the principles of space there, determining the distances between building, and which streets became thoroughfares or side streets.'

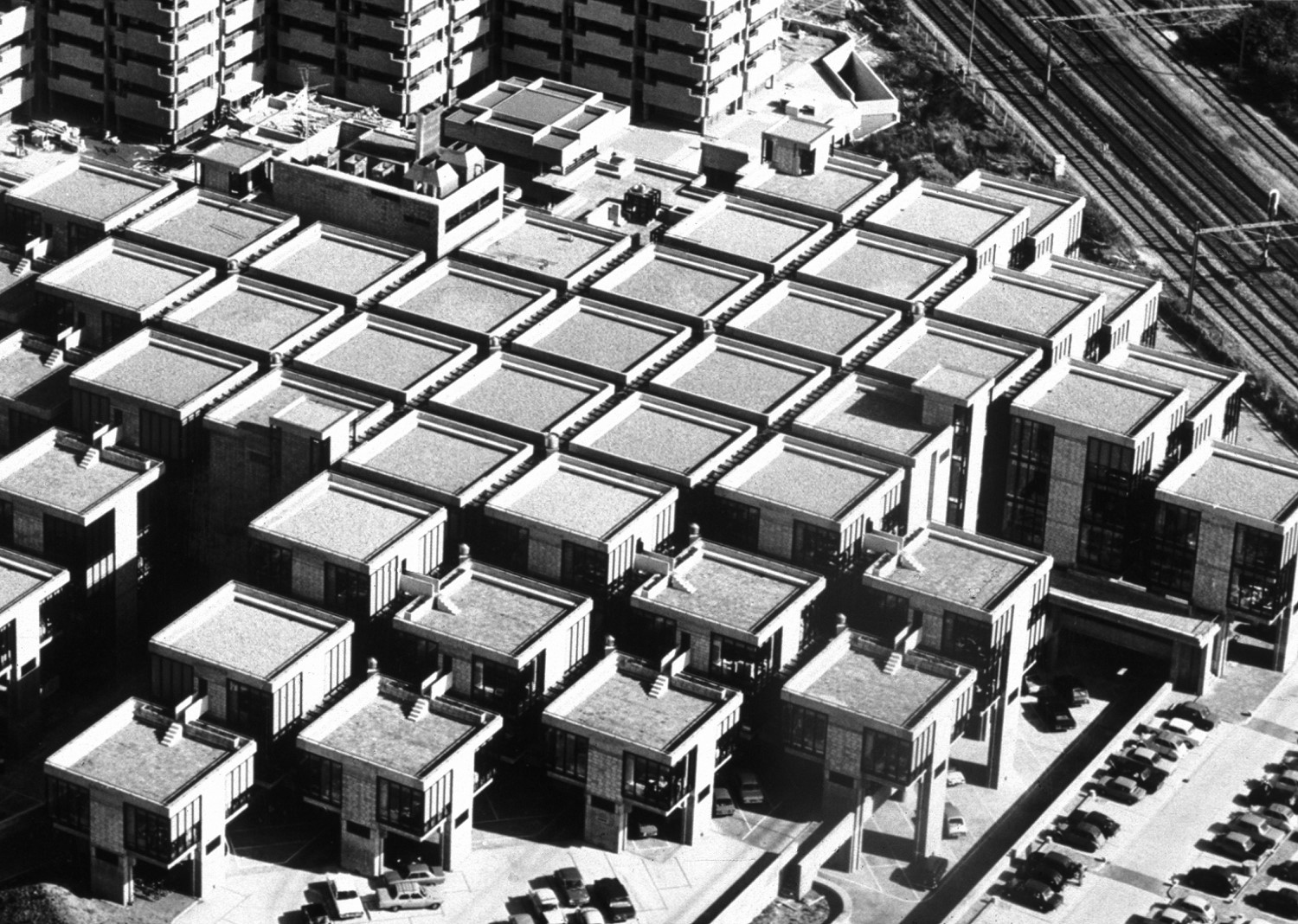

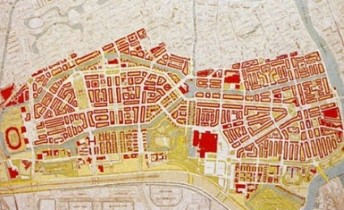

Plan Zuid

Herman Hertzberger [right].

'The area is full of details that we now find, with our no-nonsense approach, a little over-the-top, perhaps even a little pointless, but which are nevertheless part of the architecture and its spatial and plastic repertoire. The block next to ours, also on Churchill-laan, comes to mind. At the foot of the stairs outside, there were these huge eggs made of natural stone. I still remember being fascinated by them as a small child, wanting to climb on them and I remember exactly how it felt to sit on them. Some peolpe might ask: who thought of putting something so idiotic at the foot of a staircase, right there on the street? I am certainly not suggesting that architects should create more of these kinds of things, but the fact remains that although not intrinsically useful, objects such as these often leave a lasting impression on a small child. You could say that as a boy in Plan Zuid I was able to reconcile myself with the buildings that I saw despite the fact that I was still completely unaware of what went into their making. This was also made possible by an indulgent mother who let me climb any staircase I happened to come across on the street. All this led to buildings - which already attracted me - becoming part of my familiar surroundings.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Plan Zuid by Berlage, 1914.

'The block at the intersection of Beethovenstraat and Apollolaan, by J.F. Staal who also designed the ’Wolkenkrabber’ on Victorieplein, was part of our territory when we played outside. Those wonderful steel bays, which are still attached, with oval peepholes on the sides. Although I did not yet know the meaning of the word architecture, it apparently did get through to me one way or another. I was fascinated by the steel bays, and it struck me that they were constructed in a different style than the building itself, that they were more modern. I remember thinking that it did not seem right for there to be oval holes in them. If you stood there, on the corner of Beethovenstraat and Apollolaan, yuo could see another magnificent block across the bridge on J.M. Coenenstraat. Housing, also by J.F. Staal. Those two blocks were somehow a wonderful inspiration to me.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

J.F. Staal, J.M. Coenenstraat.

'It was only later that I realized there were other very special neighbourhoods in the world. As a youngster, I took it for granted that the whole world resembled the place where I lived. I am convinced that this has shaped me far more than all my studies put together. If I had to summarize what characterizes Plan Zuid, it would be that everything is close by; that there is no feeling of detachment anywhere; that the environment can be touched through your senses. I recently realized that as a child I felt safe in that area. I had the feeling that buildings posed no threat to me, that they were approachable, tangible. That is an incredible lesson to have learned. Its importance cannot be underestimated because inapproachability is, of course, one of the great shortcomings of our architecture.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Eerste Montessorischool

Herman Hertzberger at school.

'My earliest memories date from the time when I was able to go to school by myself, to the ‘Eerste Montessorischool’ (now ‘De Wielewaal’) in de Corellistraat, on the advice of the first wife of Dr Van Emde Boas: 'it is modern, and a trifle anarchic'. This is where everyone learnt, each in their own way, the fundamentals of being critical: be independent, don’t believe everything, and be a law unto yourself. The route took me from Churchill-laan across Boerenwetering and the Zuider Amstelkanaal and was lined with sculptures by Hildo Krop. Those sculptures made such a deep impression on me that I later sometimes thought: small children’s opinions should be given more attention when evaluating sculptures on buildings. Daily I passed A. Boeken’s Apollohal (see Alfred Roth’s The New Architecture) and the then State Insurance Bank of architect D. Roosenburg (grandfather of Rem Koolhaas) with its steel frame under construction.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam. 2007

War years

Bombardment Euterpestraat, now Gerrit van der Veenstraat (1944).

'The war erupted when I was eight years old. I witnessed the German soldiers coming down Churchill-laan in their tanks and German helmets. They marched into the city in huge numbers over the Berlage bridge, in an incredible bustle of commotion. I also experienced the bombardement of Euterpestraat (later rechristened Gerrit van der Veenstraat). That’s where the English carried out precision bombing on the Gestapo headquarters. At least it was meant to be precise, but the building was left standing. I think the bombs landed ten or twenty metres further down the street. I remember that our entire garden was full of half-burnt bank notes that had been carried up by the wind and had landed all over the neighbourhood. And of course I remember the shrapnel. We collected pieces of it and completed to see who could find the biggest one. Whenever there was an air raid my father, though forbidden to go outside, would defy the odds and look for pieces of shrapnel for us.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Apollolaan, before the house on the left was burnt down in 1944.

'I experienced the neighbourhood where I grew up - which gave me all these memories, of the house, the street - during the war years as well. Of course the war years did leave a tremendous impression on me. For example, at the intersection of Apollolaan and Beethovenstraat, I recall Germans pouring phosphorous over two villas and burning them to the ground. I was called out of bed when the villas were ablaze, a terrifying experience. Years later I would find myself standing on scaffolding at the site of one of these buildings to learn the techniques of bricklaying and pointing. That felt a little bit strange, almost symbolic. Most of my father's patients lived on the east side, in Rivierenbuurt. Most of them were German refugees, Jews that had fled Germany after 1935. Many of them were housed in the district that was still being built. My father was a very popular doctor; the fact that he was also Jewish, spoke good German and could converse with them about Goethe and music certainly helped. The refugees were all fairly musical and had cultural backgrounds, much more Bildung than the average Dutchman. It was striking; my father used to sit with them for hours, going on and on about Beethoven. Anne Frank and Renate Rubinstein were part of this group.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Montessori Lyceum - De Lairessestraat

Montessori Lyceum, De Lairessestraat.

'When I was older, I went to a school called the Montessori Lyceum. It was located on De Lairessestraat at the time, between Cornelis Schuytstraat and Valeriusplein. The school could not yet afford a new building and was still housed in a couple of very large villas with Gothic porticos. These villas were very characteristic of that area at the time. My experience at the Montessorilyceum made me realize that you can create an excellent environment in an old wealthy mansion with a great many corners and bays. It’s there that I learned that these kinds of buildings, which resemble private residences due to all their corners and peepholes, exude an atmosphere that is exceptionally well-suited for education. There were no classrooms here with forty children staring at a blackboard. Rather, this was a place where children could individually go about their work. Something that also had a major influence on me was discovering that a classroom need to be rectangular. By giving it expression you can create a periphery using the same surface area, much like those seen in wealthy homes, with a considerable variety of spaces and ample opportunity for individual activities.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier, Oeuvre Complète, 1929-1934.

'I had a few friends at the same secondary school who came from a more or less intellectual background. Among them were Arthur Isaac, the son of the Bijenkorf manager, and also Jan van Regteren Altena, the son of professor Van Regteren Altena, the art historian. I still remember going home with him to play and arriving at his house on Vossiusstraat, with walls lined with books and ladders reaching to the ceiling. There were books everywhere; this house seemed to me to have built from books. It was Jan who brought an oblong book to school one day. It was a volume from le Corbusier’s collected works. I can still feel the sensation that went through me when I first opened that book. Something suddenly awoke within me, something which had been unconsciously aroused by Boeken’s Apollohal and Duiker’s Open-air School, that was located behind our school. Although these building belonged to a familiar world, they were anomalies. And suddenly I had a book full of these strange creatures in front of me, and suddenly those white buildings, those enormous glass structures, appealed to me.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Montessori Lyceum - Anthonie van Dijckstraat

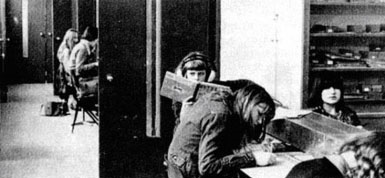

Montessori Lyceum, Anthonie van Dijckstraat.

'After a few years, our school moved from De Lairessestraat to Anthonie van Dijckstraat, to a building that impressed me enormously. I still have memories of how that building functioned. Some of its windows overlooked the street. It was a brilliant use of space. Many assets of the building were maybe not that great, but it has one very special feature. The school did not have a corridor as such, but an open aisle running along the classrooms. It did not matter that people occasionally walked by because that only happened in between classes, when the school was in state of chaos anyway. The modern buildings in this small neighbourhood made a profound impression on me. Our school was located straight across from Van Tijen, Stam and Lotte Stam-Beese’s Montessorischool and near Duiker’s Open-air School. When I later met my wife and confessed my fascination for modern white buildings made primarily out of glass, I was delighted to find that she shared this fascination. She grew up in Rotterdam among people who lived in houses built by Van der Vlugt. She not only identified with the style, but also with the mood.'

Kloos. Hertzberger’s Amsterdam, 2007

Maison de Verre, Parijs

Maison de Verre, Pierre Chareau en Bernard Bijvoet, 1931.

'Another important influence during this period was my relationship with the psychiatrist-sexologist Van Emde Boas and his wife, both of whom played a major role in my life. They were the ones to convinced my mother to send me to a Montessori school, where I was encouraged to develop all the things I had discovered on my own. But they did something else that proved to be significant. They took their son and me to with them to Paris. When she learned I wanted to be an architect, Mrs. Van Emde Boas, art historian and reviewer for De Waarheid, exclaimed: “Oh, then we have to show you a beautiful house!” That is how I was able to enter Chareau and Bijvoet’s ‘Maison de Verre’ for the first time, where there fellow sexologist, doctor Dalsace, lived. It was at that point that I realized that architecture would indeed become my profession.'

Kloos. Hertzberger's Amsterdam, 2007

Public Study Hall at the Keizersgracht

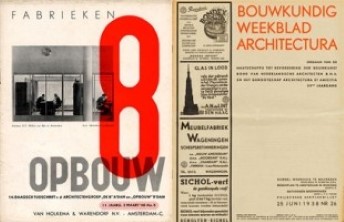

de 8 en Opbouw (1942) and Bouwkundig Weekblad Architecture (1938).

'From the moment I discovered Le Corbusier and to my introduction to the ‘Maison de Verre’ - that is to say between the age of fourteen and seventeen - I had already become preoccupied with architecture. Thanks to Le Corbusier, I took out a membership at the library on Keizersgracht, where I spent hours in the reading room systematically going through all the books on architecture from A to Z. That really kindled my interest. I read about all the various schools of architecture. The library had a wonderful collection of material about Bauhaus, Nieuwe Zakelijkheid and the Russian Constructivists. It also had bound volumes of magazines, such as de 8 en Opbouw en Bouwkundig Weekblad, which had to be read side by side since they attacked one another whenever a new building was erected. I relished the entire discussions, I loved it. And that was the kind of baggage I took with me to university.'